By celebrating local traditions—and some of the world’s steepest vineyards—winemakers uncork more sustainable trips in the Cinque Terre.

The millions of tourists who annually visit the Cinque Terre in Italy seldom realize that, in addition to the region’s candy-colored villages and sea views, this is a storied wine region with some of the world’s steepest vineyards. Its grapevines climb mountains that soar as high as 1,300 feet.

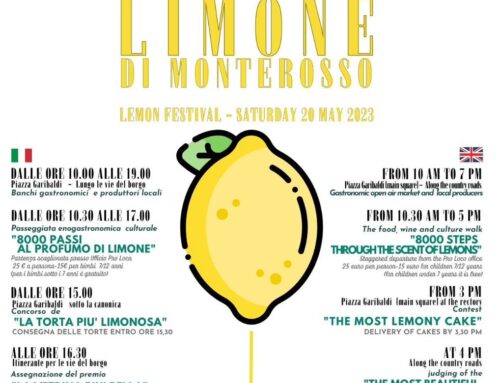

“Wine came first and the villages came next, so the history of the Cinque Terre is the history of wine,” says local sommelier Yvonne Riccobaldi. Her hometown of Manarola is one of the five villages that lends this northwestern Italian region its name. The towns—Manarola, Riomaggiore, Corniglia, Vernazza, and Monterosso al Mare—comprise Cinque Terre National Park, which spans nearly ten miles of rocky coastline between the seafaring cities of Genoa and La Spezia.

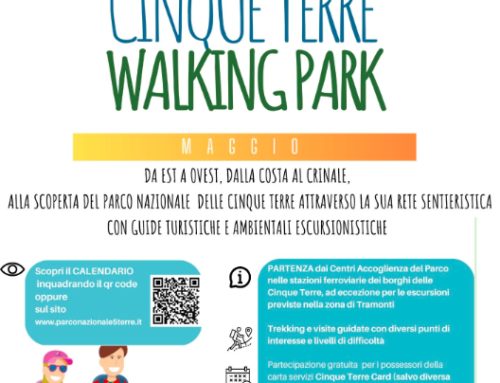

An extensive network of scenic former mule trails links villages with vineyards enclosed by hand-hewn stone walls built as early as the 11th century. But crumbling terraces and a dwindling population mean that this fragile ecosystem is endangered.

Local winemakers and other businesses are focusing on sustainable and heritage tourism to bolster the economy and environment of the Cinque Terre. Here’s how to drink it in.

Wines that tell a story

“We have about 30 small producers in the Cinque Terre, producing white wines made from Bosco, Albarolo, and Vermintino grapes,” Riccobaldi tells me as we sip and swirl at A Pié di Campu, her Manarola restaurant and tasting room. The yields are small, too: the average vineyard puts out just 5,000 bottles a year.

These whites are made to drink young. But the region’s most emblematic wine is the rare and expensive sciacchetrà (shaak-eh-tra). The complex, aged dessert wine—redolent of apricots, almonds, and candied orange peel—is rooted in ancient times, when the Greeks colonized the Mediterranean basin. Today, Riccobaldi says, families enjoy sciacchetrà at weddings and other celebrations.

“Thanks to grassroots efforts,” says Riccobaldi, “almost all of the Cinque Terre restaurants now support local vineyards.” These include creative, contemporary spots such as Rio Bistrot in Riomaggiore and tiny, family-owned Cappun Magru, on Manarola’s church square. At the latter, the owner’s son tells me that the minerality of the region’s wines goes well with local dishes, from his mama’s seafood lasagna to spaghetti with local anchovies served at nearby Ristorante Miky.

(Learn why this little known Italian region has some of the country’s best wine.)

Vineyard tours or wine tasting rooms like Riccobaldi’s or Ghemé in Riomaggiore also reveal local life and wine culture. Book in advance, though, because all are small and family owned. Take Cian du Giorgi, a restored vineyard in the medieval village of San Bernardino, where a French-Italian couple produces wines aged mainly in Ligurian amphorae.

Although some Cinque Terre cantinas, like Vétua, in Monterosso, host tastings in the villages, others, like Azienda Lìtan, entail a trek up from the port to their vineyard. This gives visitors a feel for the hard labor required to make wine in a region where rugged terrain prevents machine harvesting and, in most places, access by road.

Challenges to the vines and the culture

Winemakers face steep challenges in the Cinque Terre. “It takes about 2,000 hours a year to cultivate one hectare of grapes here,” says Giancarlo Gariglio of nonprofit Slow Wine Italia. “In Napa Valley, it takes about 250 hours.”

“Ninety-five percent of our terraces have been abandoned over the past century,” he says. This is because the Cinque Terre lost about half of its population in the last decade. Grape growers and farmers abandoned their rugged land and villages for easier, better paying work in tourism or the nearby shipyards of La Spezia and Genoa.

Unfortunately, population decline combined with staggering growth in day-trippers—mainly from large cruise ships—threatens to erase traditional culture and transform the Cinque Terre into another Venice.

“Even though most of us now live from tourism, we are overwhelmed,” says Christine Godfrey, an American who, with her husband, Nicola, owns Cinque Terre Trekking. In their spare time the couple work with village elders to uncover and restore portions of the stone trails once used by Nicola’s ancestors. Their goal is simple, Nicola says: “to encourage visitors to explore beyond the main streets and understand the impact of our handmade walls.”

Growing slow tourism

One way to achieve this goal, many believe, is to funnel more tourist revenue from the national park entrance fees back to the land via wine tourism. “When you sell a bottle of wine, you are selling the territory behind that bottle, the culture of that territory, and the history of the landscapes,” says Massimo Garavaglia, Italy’s former minister of tourism. “Wine-related tourism has a component in environmental sustainability.”

Thankfully, a new approach to tourism is taking root. Christine Godfrey is raising awareness of the Cinque Terre backcountry and its wine terraces by organizing an annual ultra-marathon event, SciaccheTrail, followed by a wine tasting. But any visitor with stamina and sturdy shoes can hike her favorite path from Manarola to Corniglia on the stone staircases and paths vintners have used for centuries.

In Riomaggiore, Heydi Bonanini has been rebuilding the stone walls on his family’s land, Possa Farms, since 2004. Today, he shares stories of regional winemaking with local schoolchildren and visitors alike.

Davide Zoppi organizes informative ambles followed by guided tastings and bucolic picnics in his family vineyard, Cà du Ferrà, just outside of the Cinque Terre park. Since he traded his career as a lawyer for his native village in 2017, Zoppi and his husband have expanded their white wine production.

Their dream, he tells me, was to replant the original grape, Ruzzese, used to makesciacchetrà—the sweet wine the popes adored. The couple accomplished their goal, and I close out my trip with a honeyed glass of their liquid history.

“As winemakers, we are the sentinels of the territory,” Zoppi says. “It’s our responsibility to rebuild, maintain, and transmit this heritage.”

Ceil Miller Bouchet is an Iowa- and France-based writer who specializes in wine and food coverage.

Chiara Goia is an Italian photographer and a National Geographic Explorer.